Airway management is a set of medical procedures performed to prevent airway obstruction and thus ensure an open path between a patient’s lungs and the atmosphere.

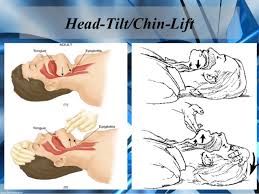

Suctioning and anatomical positioning such as the head tilt, chin lift or jaw thrust will in most circumstances relieve these obstructions regardless of the anatomy responsible for causing them.

Anticipating and recognizing respiratory decompensation is only the first step in emergency airway management. Practitioners must be familiar with the indications and techniques for airway intervention and how to anticipate a difficult airway. The basic approach includes assuring airway patency, protection from aspiration, and providing adequate oxygenation and ventilation.

Ventilation and oxygenation are separate physiological processes. Ventilation is the act or process of inhaling and exhaling. To evaluate the adequacy of ventilation, a provider must exercise eternal vigilance. Chest rise, compliance (as assessed by the feel of the bag-valve mask), and respiratory rate are qualitative clinical signs that should be used to evaluate the adequacy of ventilation.

Oral airway devices: Oropharyngeal airways will relieve soft tissue obstruction of the posterior airway by displacement of the tongue and soft tissue anteriorly. They should only be used in the unconscious patient as vomiting, aspiration and laryngospasm may otherwise occur.

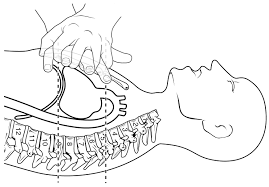

Nasal airway: The nasopharyngeal airway is another option. These are placed in either nasal passage and allow unobstructed routes for ventilation through the nose to the hypopharyngeal area. They tend to be less stimulating than the oral airway but can cause epistaxis.

The base of the nasal passage is relatively flat and parallel to the roof of the mouth. When inserting the airway, lift slightly on the tip of the nose with the free hand, and place the lubricated airway straight into the passage with the bevel against the nasal septum, not upward as is the natural tendency. This limits contact with the turbinates and hopefully avoids the resultant nosebleed.

The airway should be constructed of a soft, flexible material, and apply a water-based lubricant such as KY jelly prior to insertion.

There are two primary insertion techniques:

- The airway device may be inserted sideways or upside-down and, once it is well into the mouth, rotated and advanced in to the full position

- A tongue blade can hold the tongue in a down and forward position until the airway is in place

May 13, 2012 – Uploaded by Oxford Medical Education

Types of airway obstructions

The types of airway obstructions are classified based on where the obstruction occurs and how much it blocks.

- Upper airway obstructions occur in the area from your nose and lips to your larynx (voice box).

- Lower airway obstructions occur between your larynx and the narrow passageways of your lungs.

- Partial airway obstructions allow some air to pass. You can still breathe with a partial airway obstruction, but it will be difficult.

- Complete airway obstructions do not allow any air to pass. You cannot breathe if you have a complete airway obstruction.

- Acute airway obstructions are blockages that occur quickly. An example of an acute airway obstruction is choking on a foreign object.

- Chronic airway obstructions occur two different ways. These can be blockages that take a long time to develop, or blockages that last for a long time.

What causes an airway obstruction?

The classic image of an airway obstruction is someone choking on a piece of food. But that’s only one of many things that can cause an airway obstruction. Other causes include:

- inhaling or swallowing a foreign object

- a small object becoming lodged in the nose or mouth

- allergic reactions

- trauma to the airway from an accident

- vocal cord problems

- breathing in a large amount of smoke from a fire

- viral infections

- bacterial infections

- a respiratory illness that causes upper airway inflammation, called croup

- swelling of the tongue or epiglottis

- abscesses in the throat or tonsils

- a collapse of the tracheal wall, known as tracheomalacia

- asthma

- chronic bronchitis

- emphysema

- cystic fibrosis

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Who is at risk for an airway obstruction?

Children have a higher risk of obstruction by foreign objects than adults. They’re more likely to stick toys and other small objects in their noses and mouths. They may also fail to chew food well before swallowing.

Other risk factors for airway obstruction include:

- having severe allergies to insects such as bees, or foods such as peanuts

- birth defects or inherited diseases that can cause airway problems

- smoking

- people who have a difficult time swallowing food properly, such as those who have neuromuscular disorders

The fact is that all providers involved with airway management need a reality check. With so many intermediate and advanced airway skills being practiced, such basic skills as BVM ventilation are deteriorating. It must be understood that these fundamental airway skills will perish over time if not routinely practiced. In addition, we must realize there’s been a sea change with respect to airway management in the field. After years of resuscitation research, we now realize less may actually be more.

Uninterrupted chest compressions with little emphasis placed on ventilation is the latest cardiocerebral resuscitation skill. Advanced procedures, such as intubation, central line placement and administration of all of those “wonder drugs,” may not be best for our patients. In fact, many experts now feel that basic EMTs could do more good for the airway than paramedics. To help you understand these concepts and make that difference for your patients, we’re revisiting the “must-know” basics to make you a better airway manager.

American Heart Association Guidelines for CPR

Suctioning is a method of removing mucous from the lungs. People with a spinal cord and/or brain injury may have problems breathing due to congestion. The muscles that help with breathing and coughing may not work well. Suctioning will help keep the airway clear.

When patients are unable to mobilize their secretions, you may need to suction any secretions from the oropharynx and/or trachea to maintain a patent airway. Patients may be unable to clear their own airway due to a number of different problems, including neuromuscular disease, sedation or neurological deficits, such as a CVA. In addition, patients with an artificial airway, such as those who have been intubated, usually require suctioning while they are on a ventilator.

Suctioning may be done through an endotracheal tube, tracheostomy tube or through the nose or mouth into the trachea. Although each procedure is slightly different, indications, supplies, procedures and risks are similar.

Contraindications to Suctioning

Most contraindications are relative to the patient’s risk of developing adverse reactions or worsening clinical condition as a result of the procedure. When indicated, there is no absolute contraindication to endotracheal suctioning. Abstaining from suctioning in order to avoid a possible adverse reaction may, in fact, be lethal.

Dislodgement and introduction of bacteria into the lower airway through the tracheal tube have been demonstrated. Trauma to the airways is also possible. In general, however, deterioration in respiratory, cardiovascular and other physiological systems are potential complications of any suctioning procedure. Examples of these adverse events during suctioning include plugged or dislodged endotracheal tubes, loss of ventilation, hypoxia and patient discomfort. Pediatric patients are particularly prone to preventable complications during suctioning. The risks to pediatric patients during suctioning include airway trauma, hypoxemia and migration of the endotracheal tube.

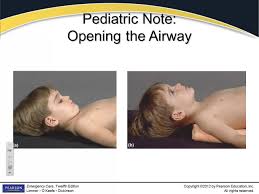

The first anatomical difference between the pediatric and adult patient becomes important when positioning the child prior to or immediately after the induction of anesthesia. The head of a pediatric patient is larger relative to body size, with a prominent occiput. This predisposes to airway obstruction in asleep children, because the neck is in flexed when they lie on a flat surface. A folded towel is often required as a shoulder roll to achieve a neutral position of the neck and open up the airway. This is demonstrated visually in. The larger occiput combined with a shorter neck makes laryngoscopy relatively more difficult by providing obstacles to the alignment of the oral, laryngeal, and tracheal axes.

Please feel free to email us any questions, comments and anything you may like us to post as part of your training. GOOD LUCK…